SUBMISSIONS OF THE ISLAMIC WOMEN'S COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (IWCNZ) TO THE ROYAL COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO THE ATTACK ON CHRISTCHURCH MOSQUES ON 15 MARCH 2019

PART THREE: RECOMMENDATIONS

Dated: 2 December 2019

WCNZ Ms Anjum Rahman Ms Aliya Danzeisen Dr Maysoon Salama 1

COUNSEL ACTING

Frances Joychild QC

Level 7, 20 Waterloo Quadrant

Auckland City 1010PO Box 47947, Ponsonby 1144P: 09 309 7694E: frances@francesjoychildqc.co.nz Research (Natalie Devery/Sylvia Bell)

----

1 Dr Salama reserves the right to clarify or supplement these submissions. She has suffered the loss of her son and been on the Hajj so has not have time to fully review the document at this date.

Index

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

Introduction

Reforms to protect against future public service delivery failures Recommendations

Support to the Muslim Community in New ZealandRecommendations

Security for the protection of all communities Recommendations

Countering Islamophobia/ Hate Speech and Hate Crimes Recommendations

Reparations Recommendations

Education: Addressing Islamophobia, cultural ignorance and bullying Recommendations

Immigration: Creating stability and alleviating stress Recommendations

Employment Recommendations

3

17

18

18

19

28

29

37

38

39

39

40

41

41

42

INTRODUCTION : RECOMMENDATIONS OF IWCNZ

1 These recommendations follow the submissions of IWCNZ to the Commission dated 29 August 2019 and to the meeting between Commissioners and IWCNZ Council members Ms Danzeisen, Ms. Rahman and Dr Salama on 17 September 2019. They respond to Terms of Reference 2 (c) and 2 (d) of the Order of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019, namely:

(c) whether there were any additional measures that relevant State sector agencies could have taken to prevent the attack; and

(d) what additional measures should be taken by relevant State sector agencies to prevent such attacks in the future.

2 The terms of reference clarify that recommendations may concern legislation (but not firearms legislation), policy, rules, standards, or practices relevant to the terms of reference, that are consistent with the widely accepted values of a democratic society. Recommendations are made in subject areas A to H.

(c) whether there were any additional measures that relevant State sector agencies could have taken to prevent the attack; and

(d) what additional measures should be taken by relevant State sector agencies to prevent such attacks in the future.

2 The terms of reference clarify that recommendations may concern legislation (but not firearms legislation), policy, rules, standards, or practices relevant to the terms of reference, that are consistent with the widely accepted values of a democratic society. Recommendations are made in subject areas A to H.

A Reforms to protect against future public service delivery failures

3 IWCNZ refers to its submissions of 29 August 2019 at paras 286 to 336. It says the public service failed to deliver services to address the urgent and pressing needs of the marginalised vulnerable Muslim community in the period 2015 – 2019, despite multiple requests for support made to the highest levels by members of its executive council, and despite the United Nations having developed a Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism in 2015, which required governments to provide the very type of support programmes IWCNZ were seeking from it. 2

4 With a couple of exceptions, there was a collective inertia within the public service, inability to understand and comprehend the issues facing the Muslim community, lack of vision, lack of know- how, and a lack of innovation or motivation to address them. 3

5 The failure of the crossgovernment working group, established after the March seminar, and the fact that DIA appointed a report writer (XXX XXXX) to go to Hamilton to assess opportunities in Hamilton as a solution to the calls of the community for national assistance are shining examples of the starkness of the system failure.

6 The public sector employees who IWCNZ liaised with over that period had (or were perceived as having) entirely inward looking lines of responsibility and accountability. They consulted inordinately with IWCNZ, WOWMA and others but, despite expenditure of public funds, achieved very little. 4

7 There was no hint from anywhere that the public servants might be accountable to the Muslim community as well as their superiors for delivery of CVE. There were regular staff changes and consequently no institutional knowledge developed. IWCNZ had to continually update and upskill new staff. 5

Those public sector employees who were Muslim and given responsibility in this area, were trying to implement a programme without the necessary engagement and co-design with the community. Agencies appeared to be competing for resources and wanting to shore up their own departments. Indeed, the day after the attacks, the only relevant fact that Ms Little felt necessary to advise Ms Danzeisen of was that OEC now had more money.

8 In the future, projects that have been developed for a specific vulnerable community must involve that community. This requires more than consultation with them without any further interactions. There should be real engagement throughout the consultation process to identify a joint plan. Where the community disagrees with a planned project or decision in relation to that community, then the public servants should pause, listen and reflect. They need to value the lived experience of that community. The government must be transparent in who it engages with from a community. They must be persons with knowledge and experience and representing the diversity of the community, even if they are perceived as being 'difficult'.

9 Funding for a community should, where at all possible, be devolved to that community so that the community is empowered to determine its own destiny. Investment should be in programmes that bring communities together. Potential pitfalls in resourcing should be identified and avoided.

10 Taking account of impressions drawn from overseas practices, IWCNZ contends that there is a risk in that public servants in the CVE areas often move into roles as independent contractors to the public service in the particular public sector they previously worked. The perceived risk is that this could influence solutions related to CVE that would benefit them as contractors at a later date. Recognising this potential compromise to independent advice being given, a 'restraint of trade' type clause in contracts in the CVE area is recommended. This would mean that in New Zealand, an employee could not be contracted to work in the field they were working in previously for a period of between 2 to 5 years.

11 An important mechanism that oversees the public sector and holds it accountable to the public is the Ombudsman. Likewise, the Inspector-General of Security holds the security agencies accountable. It is vital that there is ongoing adequate funding of these review organisations. This has not been the case in relation to the Ombudsman where there have been very long delays in complaint investigations over the past decade although these appear to have improved under the current Ombudsman. 6

However, the Ombudsman does have a significant number of roles and responsibilities.

12 IWCNZ suggests there should be an ‘independent ethics board’ or body overseeing the entire CVE area, including security considerations. Such an agency would act of its own motion to conduct random audits of those government actors who have responsibilities in this field so as to ensure the programme is on task. It would also deal with complaints, including any in relation to surveillance of those within the Muslim community.

----

2 See para 75 – 78 Submissions of IWCNZ dated 29 August 2019. Note also the NZ government had been on notice since 2006 that it needed to develop a counter terrorism strategy. (see para 74) 3 The exceptions were NZ Corrections and MSD. See Part 2. Note also that though these submissions focus on IWCNZ there have been other significant public service delivery failures in the last 12 months alone. See Martin and Mount’s report on ‘The State Sector Act Inquiry into the Use of External Security Consultants by Government’ 18/12/2018. They found several breaches of the Code of Conduct and a widespread Government’ 18/12/2018. They found several breaches of the Code of Conduct and a widespread misunderstanding as to privacy and security obligations. https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO1812/S00215/external-security-consultants-inquiry-findings.htm. See also the Privacy Commissioner’s Report of his investigation into MSD’s benefit fraud investigations describing MSD practices as ‘intrusive, excessive and inconsistent with legal requirements’ 16.05.2019 www.privacy.co.nz 4 They did not report back on their intended actions. They gave Muslim community members advice they already knew. They lacked basic knowledge and competence in CVE. They were ineffective in their efforts on the ground in Hamilton. 5 Ms Danzeisen recalls a government employee responding to a talk she gave about the need Muslim parents had to prepare their children for harassment after an overseas terrorist attack, by saying that he had not even thought of that.

6 However it is noted in the 2018/19 annual report that large proportions are not actually investigated by the Ombudsman.

2019 proposed Public Service legislative reforms

13 It is timely that the Minister has announced that the public service is to be restructured. Consultations have taken place and a bill is about to be introduced into Parliament. IWCNZ endorses the recognition by the government and State Services Commission of the need for reform of the public service. At the time of writing these recommendations, the promised Public Service Bill has not been introduced into the House although it was hoped this would happen before the end of 2019 and be enacted by the end of 2020. 7

14 However, Cabinet papers and State Services Papers, including an ‘Impact Statement’, are available and illustrate the direction the Government is intending to take. The Impact Statement reports the results of consultation and decisions made on the content of the proposed new legislation. In this statement the SSC has recognised that the State Sector Act reforms of the 1980’s have created problems. 8

It identifies 6 key problems arising from the current structure. These are: 9

1 A narrowing of each department’s focus to its own particular outputs. Officials are incentivised to focus on their own agency rather than instilling a larger sense of the wider Public Service with a unifying common mission. They are even focused to compete with other departments.

2 Closely related services are provided by different departments and people find themselves having to interact with multiple agencies to get relevant information to address a single problem.

3 The government has difficulty addressing complex social issues that span agency boundaries. Dealing with the issues effectively requires agencies to work together in a coordinated manner.

4 There is a high variation in employee terms and conditions which made it difficult for employees to cross departments with the result that employees identify with their own department rather than a unified public service serving the interests of all New Zealanders.

5 The culture of frequent structural changes and reorganisations has resulted in productivity dips, loss of institutional memory and consequent issues with the depth of experience available to address the problems of the day and provide government with best advice. 6 There was not a sufficient centre by which to coordinate effort or guarantee adherence to the values and ethics of loyalty and impartiality.

15 The impact statement records that the objectives of the reform are to deliver better outcomes and services, create a modern and agile and adaptive New Zealand Public Service and affirm the constitutional role of the Public Service in supporting New Zealand’s democratic form of government. Further, that the planned interventions are intended to provide the ability to effectively join up around citizens to respond to cross-cutting issues, generate alignment and interoperability across the Public Service and to establish behavioural and cultural foundations for a unified Public Service. 10

It is intended that the legislation itself makes explicit recognition of the value of diversity and of fostering inclusiveness. Chief Executives will be responsible for giving effect to these values and the Commissioner will have an oversight role. Besides the legislation, the reforms will be effected by way of a change programme driven by the new Public Services Commissioner and Chief Executives of the Public Service.

----

7 IWCNZ notes that Minister Hipkins has not consulted with it as part of its consultations prior to the drafting of a bill, despite requests to do so from Jan 2018. It queries whether the SSC consultation involved members of the public or recipients of services at all. 8 Impact Statement: State Sector reform. 17 June 2019. p 5 The system incentivises separate agencies to be enterprising about their own resources, focused on the production of outputs, but not incentivised to connect with others or focused on achieving better outcomes.9 Ibid p 6-710 P 12

Proposed legislative principles

16 Five public service principles have been identified to guide a new legislative regime and will themselves be embedded in the legislation. There are:

Proposed legislative purpose 17 It is noted that the original proposed purpose that was the subject of consultation for the Impact Statement, commenced with the words : 11

- political neutrality

- free and frank advice to Ministers

- merit-based appointment

- open government

- stewardship

Proposed legislative purpose 17 It is noted that the original proposed purpose that was the subject of consultation for the Impact Statement, commenced with the words : 11

The NZ Public Service exists to improve the intergenerational wellbeing of New Zealanders, including by-

- Delivering results and services for its citizens

18 That proposed purpose was rejected as being too wordy and complicated. Instead a new post-consultation purpose has been developed and will be put in legislation. This removes the people/customer focus almost entirely. It reads:

The Purpose of the New Zealand Public Service shall be to support constitutional and democratic government; enable current and successive governments to develop and implement their policies; deliver high quality efficient Public Services; safeguard the long-term public interest; and enable active citizenship.

IWCNZ response on proposed principles and purpose

19 IWCNZ says that the principles - as they now are - omit to deal with a key failure of the public sector in the situation to which these recommendations relate. This is that it was entirely devoid of a ‘member of the public’ or ‘customer’ focus. 12

What is needed is a principle highlighting that the focus of the public service should be outwards, towards the ‘citizen clients’ or ‘citizen customers’. Hence, a new principle should be added: that of service.

20 In a similar way, IWCNZ says that the proposed legislative purpose is not outward looking towards the people it is serving. Apart from the words ‘enable active citizenship’, it makes no reference to the overriding need to ‘serve the public’ and put their needs first. After all, the public service is fully funded by the public, through various taxes gathered for the very purpose of serving them. Hence, it is recommended that after ‘to develop and implement their policies’, the purpose provision should read, 'serve the people of New Zealand by delivering high quality Public Services, enabling active citizenship and safeguarding the long-term public interest.'

21 The ‘merit based appointment process’ is often one that works against those community members who are marginalised. While minorities may not have had access to the quality of education, networking and connection opportunities to compete ‘on merit’, they do have other valuable and unique skills and qualities they bring to the public sector. ‘Merit based’ must be broadened to recognise those skills and qualities. 13

Non -legislative reforms

22 Whilst the orientation to service of the public is needed to be explicitly provided for in the Principles and Purpose sections, other steps need to be taken to alter the working culture of the public sector. IWCNZ submits that:

(a) guidance on the steps required to create a service oriented public service should be developed by the Public Service Commission and draw from the research and advice paper produced by Price Waterhouse Coopers: The Road Ahead for Public Service Delivery. Delivering on the customer promise. 14

The paper is a global effort drawing on experiences of multiple diverse public sectors internationally. The paper concludes that the way ahead requires a new service delivery model that is entirely customer focussed.

(b) A human rights matrix, as described by the Human Rights Commission, be adopted to guide how policy might best be developed.

23 Each of these is discussed in turn. 15 Both are directly relevant in addressing the glaring failures in the New Zealand public service in their dealings with the Muslim community prior to the attacks. 16

----

11 P 20/21 Impact Statement.

12 It notes that this was in earlier papers. F ,or example see the paper to the Chair of the Cabinet Government Administration and Expenditure Review Committee, para 2, Executive summary: It (the legislative change) is about reconnecting with the spirit of service to the community and unifying the public service around a common purpose, principles and values. These will ensure the public service operates with integrity and earns the trust, confidence and respect of New Zealanders.

13 Hence, EEO programmes, which have had success for women, must be continued in the public service to progress and support minorities.14 The road ahead for public service delivery. Delivering on the customer promise. Public Sector Research Centre (PSRC). PriceWaterhouseCoopers. (PWC) 18 April 2015. The PSRC is PWC’s centre for insights and research into best practice in government and the public sector, including the interface between the public and private sectors. The Centre has a particular focus on how to achieve the delivery of better public services, both nationally and internationally. While IWCNZ does not necessarily support the concept of the public being ‘customers’ the guidance is nevertheless very valuable. 15 IWCNZ also refers to The Principles of Public Administration: Chapter 5, Service Delivery published by Sigma (a joint initiative of the OECD and EU). Undated but most likely 2015. Again this emphasises as an essential principle the need to be oriented to delivering to the public. It is called ‘citizen oriented’ in this chapter: Principle 1: Policy for citizen-oriented state administration is in place and applied. Sub para 1: A policy exists to design public services around the needs of the user16 Note also the Sigma Papers no 27. These working papers are the work of the OECD and European Union and were prepared as guideline advice for Eastern European Countries wanting to join the EU as to what would be expected of their civil service. Among the conclusions are that the civil service is one main element of public administration; but it is such a major element, public administration and civil service are often considered to be synonymous. Within member states Civil Service Values are legally binding; regulating the civil service goes beyond merely regulating the labour relationships between the state and its employees – it concerns regulating one of the state's powers in a broad sense. Administrative law principles inspire the decision-making of public managers and pattern the behaviour of the civil service as a whole. https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5km160zwrd7h-en

PWC Report : Delivering on the Customer Promise

24 The report says that Customer focus is often challenged by public sector culture, hierarchical organisational structures and differing public sector priorities. 17

To deliver on the ‘customer promise’ requires five strategic enablers: 1 Understand your customer (Customer-centricity;) 2 Pull down the walls (Connected government)3 Empower your institution (Build capacity)4 Realise benefits through appropriate models (Deliver the promise)5 Continuously improve (Innovate).

25 Being customer centric requires that customer insight be used to inform effective customer delivery: 18 Public sectors are advised that the delivery process must be from the customer’s point of view, and using co-creation where value is co-created by the organisation and the customer. 19 Services are to be delivered based on the needs and preferences of the customer and there must be multiple delivery channels. 20 The competence, know-how and empowerment of staff to develop new models of service delivery must be developed. Staff training and development are critical. 21

25 Being customer centric requires that customer insight be used to inform effective customer delivery: 18 Public sectors are advised that the delivery process must be from the customer’s point of view, and using co-creation where value is co-created by the organisation and the customer. 19 Services are to be delivered based on the needs and preferences of the customer and there must be multiple delivery channels. 20 The competence, know-how and empowerment of staff to develop new models of service delivery must be developed. Staff training and development are critical. 21

----

17 This is consistent with the NZ government’s experience and IWCNZ’s experience. 18 See p 17, Chapter 03 Understand your customer: Customer is king in the public sector too:In the public sector, in contrast to the private sector, it is crucial to understand the nature of the policy outcomes required – as well as the customer outcomes. Unlike the private sector, where the organisation is at liberty to define its customer segments, the public sector is required to service numerous diversified customer segments. It is therefore essential to develop clear policies to meet the needs of each segment. The needs of the various segments can be quite distinct and will be driven by multiple factors, including demographic attributes such as age, education, income and more attitudinal factors such as beliefs, values and willingness/ability to engage with government. Understanding them all is critical to the development and implementation of a customer-centric service delivery strategy… The public sector is required to satisfy the rights of its entire customer base - equally and to acceptable standards. There needs to be a clear strategy for ensuring the inclusion of all the segments of society that might be served. This subject is highly topical.19 Examples of how this is achieved include responding to customer feedback and seeking the involvement of customer segments in the development of services to achieve customer-centric outcomes. 20 For example: the delivery of services may be by post, telephone, face to face, directly through government or indirectly through intermediaries such as voluntary organisations. In designing a channel strategy, care should be taken not to force customers in any one direction. Because of the diversity of their customer base, public sector organisations need to focus on creating multiple delivery channels. 21 See p 32 PWC ‘…But in the public sector senior personnel often tend to focus much of their efforts on policy making in response to political decision-making, delegating responsibility for implementing these policies and failing to take into account the end impact on ‘customer experience’ during their design.

A Human Rights Approach to policy development

26 A human rights approach is a conceptual framework based on international standards developed by the United Nations to promote and protect human rights. The approach is used principally in relation to policy development although it has been used to evaluate judicial decision making. As adapted for New Zealand by the Human Rights Commission in 2004, 22

The approach involves:

27 Since 1 Feb 2002, the New Zealand Government has been bound by Part 1A of the Human Rights Act which requires it to comply with the rights and obligations set out in the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act. It can be held to account before the Human Rights Review Tribunal and higher courts when it breaches these. It was expected, by the then Attorney-General, Margaret Wilson, that this would create a ‘human rights compliant culture’ within the public service. As cases against various departments have illustrated since then, this has not occurred and an antagonistic approach has, instead, been created. 23

28 If a human rights approach had been adopted by the Departments with whom IWCNZ was engaging, it is likely there would have been very different outcomes in the delivery of the respective and much-needed public services to the Muslim community. Each step in the approach is discussed briefly below.

(i) Standards in the international human rights treaties 29 When a country ratifies an international human rights treaty it makes a commitment to give effect to the standards in that treaty. The UN has consistently endorsed the notion that international human rights law should be understood as providing the domestic framework for - among other things - the operations of government and the interpretation exercises undertaken by the courts. However, while the courts have made significant strides in using international human rights treaties to construe legislation and the exercise of discretion for example, the public service has not followed suit. Though a report is routinely undertaken as to the compliance of proposed new legislation with the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act, and is required to accompany its introduction to the House, that is an after the event exercise. Human Rights obligations, values and guidance have not been used as a framework for the development of policy. 24

30 One example is given of the difference this may have made to the Muslim community. Had a human rights approach been part of the culture of the Public service when concerns about online Islamophobia and hate speech were being expressed, then the public sector agencies would have had a framework in the form of Article 19, General comment and the Rabat Plan of Action. 25

(ii) Participation 31 The UN Guiding Principles specifically refer to the need for “meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders." 26 Participation is the idea that those affected by a decision should be able to have a say in the outcome. It allows marginalised persons and communities who would otherwise have no means of directly influencing the public sector and policies that impact upon them and their communities, to do so. 27 The importance of participation to a healthy democracy is well recognised and is put well by Professor Smillie in 1978: 28 Providing citizens with an increased sense of involvement in the administrative process tends to allay suspicion that decisions of governmental regulatory bodies tend to unduly favour the organised entrenched interests of regulated enterprises at the expense of more diffuse and less organised interests such as those of consumers, environmentalist and recreational groups.

(iii) Non–discrimination 32 UN comment consistently refers to ensuring policies are not discriminatory and do not inadvertently favour or prejudice one group over another. Frank LaRue, the Special Rapporteur in 2010, on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of expression, noted that stereotypes and prejudice against ethnic, racial, linguistic and religious groups are the result of racism and discrimination or the erroneous application of national security and anti-terrorism policies. It is essential, he goes on, that this is recognised and countered by developing a culture based on intercultural dialogue and tolerance. 29 The public service needs to have - as a guiding principle - this need when developing policies and projects.

33 The former narrow legalistic approach to discrimination that prevailed for many years (everyone should be treated the same) has been displaced by recognition of the socio-cultural and political-legal institutions which contribute to, and sustain, the structures of discrimination. To address them requires a commitment to treat people and groups differently where necessary to ensure equal outcomes. 30

- Expressly applying the principles and standards in the international human rights instruments;

- Participation & empowerment of individuals and groups, allowing them to use rights as leverage for action and to legitimise their voice in decision-making;

- Non-discrimination;

- Accountability for actions and decisions allowing individuals and groups to complain about decisions that affect them adversely;

- Transparency;

- Vulnerability – balancing rights to maximise respect for all right-holders and where there is conflict, favouring the most vulnerable.

27 Since 1 Feb 2002, the New Zealand Government has been bound by Part 1A of the Human Rights Act which requires it to comply with the rights and obligations set out in the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act. It can be held to account before the Human Rights Review Tribunal and higher courts when it breaches these. It was expected, by the then Attorney-General, Margaret Wilson, that this would create a ‘human rights compliant culture’ within the public service. As cases against various departments have illustrated since then, this has not occurred and an antagonistic approach has, instead, been created. 23

28 If a human rights approach had been adopted by the Departments with whom IWCNZ was engaging, it is likely there would have been very different outcomes in the delivery of the respective and much-needed public services to the Muslim community. Each step in the approach is discussed briefly below.

(i) Standards in the international human rights treaties 29 When a country ratifies an international human rights treaty it makes a commitment to give effect to the standards in that treaty. The UN has consistently endorsed the notion that international human rights law should be understood as providing the domestic framework for - among other things - the operations of government and the interpretation exercises undertaken by the courts. However, while the courts have made significant strides in using international human rights treaties to construe legislation and the exercise of discretion for example, the public service has not followed suit. Though a report is routinely undertaken as to the compliance of proposed new legislation with the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act, and is required to accompany its introduction to the House, that is an after the event exercise. Human Rights obligations, values and guidance have not been used as a framework for the development of policy. 24

30 One example is given of the difference this may have made to the Muslim community. Had a human rights approach been part of the culture of the Public service when concerns about online Islamophobia and hate speech were being expressed, then the public sector agencies would have had a framework in the form of Article 19, General comment and the Rabat Plan of Action. 25

(ii) Participation 31 The UN Guiding Principles specifically refer to the need for “meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders." 26 Participation is the idea that those affected by a decision should be able to have a say in the outcome. It allows marginalised persons and communities who would otherwise have no means of directly influencing the public sector and policies that impact upon them and their communities, to do so. 27 The importance of participation to a healthy democracy is well recognised and is put well by Professor Smillie in 1978: 28 Providing citizens with an increased sense of involvement in the administrative process tends to allay suspicion that decisions of governmental regulatory bodies tend to unduly favour the organised entrenched interests of regulated enterprises at the expense of more diffuse and less organised interests such as those of consumers, environmentalist and recreational groups.

(iii) Non–discrimination 32 UN comment consistently refers to ensuring policies are not discriminatory and do not inadvertently favour or prejudice one group over another. Frank LaRue, the Special Rapporteur in 2010, on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of expression, noted that stereotypes and prejudice against ethnic, racial, linguistic and religious groups are the result of racism and discrimination or the erroneous application of national security and anti-terrorism policies. It is essential, he goes on, that this is recognised and countered by developing a culture based on intercultural dialogue and tolerance. 29 The public service needs to have - as a guiding principle - this need when developing policies and projects.

33 The former narrow legalistic approach to discrimination that prevailed for many years (everyone should be treated the same) has been displaced by recognition of the socio-cultural and political-legal institutions which contribute to, and sustain, the structures of discrimination. To address them requires a commitment to treat people and groups differently where necessary to ensure equal outcomes. 30

----

22 Human Rights Commission, Human Rights in New Zealand Today (2004) at 25 23 The series of cases against the Ministry of Health are one such example. Ministry of Health v Atkinson [2012] 3 NZLR 456 (CA) ; Spencer v Ministry of Health [2016] 3 NZLR 513; Chamberlain v Ministry of Health CA 460/2017 [2018] NZCA 8. In Atkinson the Ministry embarked on a full scale defence of an ill-defined policy prohibiting family members from payment for caring for family members without having undertaken any economic or other analysis into whether its policy was justified under s 5 NZBORA. In Chamberlain the Court of Appeal concluded its decision with the postscript: Postscript [90] We make two additional points. First, we note that this is the third occasion on which a dispute between the Ministry of Health and parents who care for disabled adult children has reached this Court. We hope that in the future parties to disputes over the nature and extent of funding eligibility are able to settle their differences without litigation. Second, we have referred to our unease, which is shared by Palmer J, about the complexity of the statutory instruments governing funding eligibility for disability support services. They verge on the impenetrable, especially for a lay person, and have not been revised or updated to take into account the significant change brought about by pt 4A. We hope that the Ministry is able to find an effective means of streamlining the regime, thereby rendering it accessible for the people who need it most and those who care for them.24 For example the practice of no-payment to family members for the care of an adult disabled child was never put through a human rights analysis before a decision was made inhouse to maintain it; the In Work Tax Credit was developed without reference to human rights obligation though this matter was not referred to in the decision : Child Poverty Action Group v Attorney-General [2013] 3 NZLR 729 (CA) 25 Report of the Special Rapporteur (2019) A74/48050 at [57] 26 [44]

27 Pol De Vos, Wim De Ceukelaire, Geraldine Malaise, Dennis Pérez, Pierre Lefèvre, and Patrick Van der Stuyft “Health through people’s empowerment: a rights-based approach to participation” Health and Human Rights, Vol. 11, no. 1 at 2528 Locus Standi – the Report of the Public and Administrative Law Reform Committee [1978] OtaLawRw 3; (1978) 4 Otago Law Review 141 29 Supra fn 3 at [86] 30 OHCHR Principles and Guidelines for a Human Rights Approach to Poverty Reduction Strategies (2006)

(iv) Accountability

34 The need to justify government action under s.5 NZBORA is a crucial aspect of accountability. Limitation of a right in the NZBORA is only permissible if it can be justified in a “free and democratic society”. This is effectively the same as the necessity and proportionality standard referred to in the international material (see below Appendix 1 at (g). Inherent in the concept is the implicit assumption that a government will not only take responsibility for its actions if a policy or law has the effect of infringing a right, but that it can justify doing so.

35 This “culture of justification” contributes to good governance by ensuring that citizens are entitled to seek, and receive, answers for why their rights are infringed. This can be seen in relation to freedom of speech and the prohibitions against exciting/inciting racial disharmony. It can be inferred that the legislation was considered a necessary aspect of striking the balance between appropriate protection against discriminatory conduct leading to harm to a protected group and the value of freedom of expression.

(v) Transparency 36 Transparency is closely linked to accountability. To be transparent, public sector decision makers must be able to give reasons for decisions, particularly those with the potential to directly or indirectly discriminate. They must be able to explain openly why a project or policy is or is not being adopted. Justice Wylie’s observations in Smith v the Attorney-General are apt: 31 The giving of reasons encourages transparency of thought, which of itself is a vital protection against a precious or arbitrary decision. The very process of giving reasons is likely to mean that the decision is better thought out. When reasons are given, it can be more readily seen that the decision-maker has considered relevant matters and refused to consider irrelevant matters… The person affected may well be more inclined to accept the decision if it is reasoned.

37 If details of policy implementation, funding available for projects etc are not made public then there is no ability for public servants and the public service to be held to account, whether it be by community groups, lawyers or academics. They are all vital players in ensuring a healthy, open, transparent public service. 32

(vi) Vulnerability 38 The need to protect those vulnerable groups (usually marginalised) in society is a thread running through all human rights treaties. To date, groups recognised as needing protection include those identifiable by race, colour, national or social origins, language, sex, gender, motherhood, religion, political or other opinion, property, birth or other status, indigenous peoples, descent-based groups, immigrants or non-citizens and other vulnerable persons. 39 The concept is increasingly being used to indicate a heightened susceptibility of certain individuals or groups to being harmed or wronged by others or by the State. 33 It is an important consideration in situations where popular sentiment runs against recognition of the rights of groups such as prisoners. 34 In such cases, it can be a way of imposing obligations on the State to ameliorate the harm of certain policies by tailoring the policies to meet the specific needs and concerns of vulnerable groups. Vulnerability is best understood as a “universal, inevitable, enduring aspect of the human condition” and the role of the State is to be responsive to this. 35 40 Recognition of group vulnerability allows society to understand how it reinforces inequalities resulting from broader societal and institutional circumstances and to address them accordingly. Public servants from within vulnerable group 41 The employment of persons from vulnerable communities in the public service can create ethical issues and conflicts of interest. Where the community is small in size, the government may look to those public servants to represent the views of their community, without consulting with such a community. However, that process should never be a proxy for consultation with representatives or leaders of the public servant's community. 42 Furthermore, a public servant from a minority vulnerable community should not attend meetings of community advisers without also declaring they are a public servant. The fact that a person works for the public sector should always be declared when a community panel or group is working on government policy or making recommendations to government. The same issues undoubtedly arise in all groups but particularly within small and marginalised ones. In addition, appropriate and standard practices need to be established so as to shield both the information and the person with the conflict. This is so that that public servants do not use information obtained by reason of their work in government to develop community models that compete with those models already created in the community. Conclusion 43 In conclusion, several of the obstacles in the way of the public service being able to provide a customer-centric service will be addressed in the new legislation with its focus on joined-up government. These include the obstacle of a disproportionate focus on keeping control of resources and defending individual territories 36 and the lack of data-sharing across business units and customer channels, due to various structural and technology challenges.

44 However, the changes fall short of what is needed. A mandatory ‘service to the public and every section of it’ focus must be explicitly set out in the legislation. Further, second tier guidelines must be developed that identify the ‘means’ by which the public sector focus can be changed, in practice. The PWC guidelines are pertinent and entirely on point and should be used as guidance. In addition, a human rights approach should be taken to policy and project development. If this had been in place from the time Part 1A was enacted, it is expected that IWCNZ would have had a different and more positive experience with the public services it approached for support.

35 This “culture of justification” contributes to good governance by ensuring that citizens are entitled to seek, and receive, answers for why their rights are infringed. This can be seen in relation to freedom of speech and the prohibitions against exciting/inciting racial disharmony. It can be inferred that the legislation was considered a necessary aspect of striking the balance between appropriate protection against discriminatory conduct leading to harm to a protected group and the value of freedom of expression.

(v) Transparency 36 Transparency is closely linked to accountability. To be transparent, public sector decision makers must be able to give reasons for decisions, particularly those with the potential to directly or indirectly discriminate. They must be able to explain openly why a project or policy is or is not being adopted. Justice Wylie’s observations in Smith v the Attorney-General are apt: 31 The giving of reasons encourages transparency of thought, which of itself is a vital protection against a precious or arbitrary decision. The very process of giving reasons is likely to mean that the decision is better thought out. When reasons are given, it can be more readily seen that the decision-maker has considered relevant matters and refused to consider irrelevant matters… The person affected may well be more inclined to accept the decision if it is reasoned.

37 If details of policy implementation, funding available for projects etc are not made public then there is no ability for public servants and the public service to be held to account, whether it be by community groups, lawyers or academics. They are all vital players in ensuring a healthy, open, transparent public service. 32

(vi) Vulnerability 38 The need to protect those vulnerable groups (usually marginalised) in society is a thread running through all human rights treaties. To date, groups recognised as needing protection include those identifiable by race, colour, national or social origins, language, sex, gender, motherhood, religion, political or other opinion, property, birth or other status, indigenous peoples, descent-based groups, immigrants or non-citizens and other vulnerable persons. 39 The concept is increasingly being used to indicate a heightened susceptibility of certain individuals or groups to being harmed or wronged by others or by the State. 33 It is an important consideration in situations where popular sentiment runs against recognition of the rights of groups such as prisoners. 34 In such cases, it can be a way of imposing obligations on the State to ameliorate the harm of certain policies by tailoring the policies to meet the specific needs and concerns of vulnerable groups. Vulnerability is best understood as a “universal, inevitable, enduring aspect of the human condition” and the role of the State is to be responsive to this. 35 40 Recognition of group vulnerability allows society to understand how it reinforces inequalities resulting from broader societal and institutional circumstances and to address them accordingly. Public servants from within vulnerable group 41 The employment of persons from vulnerable communities in the public service can create ethical issues and conflicts of interest. Where the community is small in size, the government may look to those public servants to represent the views of their community, without consulting with such a community. However, that process should never be a proxy for consultation with representatives or leaders of the public servant's community. 42 Furthermore, a public servant from a minority vulnerable community should not attend meetings of community advisers without also declaring they are a public servant. The fact that a person works for the public sector should always be declared when a community panel or group is working on government policy or making recommendations to government. The same issues undoubtedly arise in all groups but particularly within small and marginalised ones. In addition, appropriate and standard practices need to be established so as to shield both the information and the person with the conflict. This is so that that public servants do not use information obtained by reason of their work in government to develop community models that compete with those models already created in the community. Conclusion 43 In conclusion, several of the obstacles in the way of the public service being able to provide a customer-centric service will be addressed in the new legislation with its focus on joined-up government. These include the obstacle of a disproportionate focus on keeping control of resources and defending individual territories 36 and the lack of data-sharing across business units and customer channels, due to various structural and technology challenges.

44 However, the changes fall short of what is needed. A mandatory ‘service to the public and every section of it’ focus must be explicitly set out in the legislation. Further, second tier guidelines must be developed that identify the ‘means’ by which the public sector focus can be changed, in practice. The PWC guidelines are pertinent and entirely on point and should be used as guidance. In addition, a human rights approach should be taken to policy and project development. If this had been in place from the time Part 1A was enacted, it is expected that IWCNZ would have had a different and more positive experience with the public services it approached for support.

----

31 Smith v Attorney-General [2017] NZHC 463 (16 March 2017) citing Television New Zealand Ltd v West [2011] NZLR 825 (HC) [at 91]

32 The UN Special Rapporteur makes the point, in relation to internet companies, that lack of transparency is a major flaw in many policies and acts as a significant barrier to external review. While the rules are public, the details of their implementation, particularly of company policies at a variety of levels, are often non-existent. (45). Where company rules, for example, deviate from international standards companies should be able to explain why this is the case. The same must go for the public sector.33 R Andorno, Human Dignity of the Vulnerable in the Age of Rights, Springer (2016) 34 See Palmer, G “What the New Zealand Bill of Rights aimed to do, why it did not succeed and how can it be repaired” (2016) 14 NZJPIL. At 179 he notes that the rights of unpopular people are just as real as those who live in society’s mainstream. These situations are the very ones where rights are most needed. 35 Ibid at 1060 citing Fineman, M. “The Vulnerable Subject: Anchoring Equality in the Human Condition” 20 Yale J.L & Feminism 1,8 (2008) 36 PWC Report P 23

Recommendations – public sector reforms

1 The proposed ‘purpose’ provision in the proposed public service reform legislation be amended to explicitly provide that a primary purpose of the public sector is to serve the public as a whole and all sectors of the public of Aotearoa/New Zealand.

2 The proposed public service reform legislation provides that a key principle includes ‘service to the public’.

3 The State Services Commission (or its successor) develop mandatory guidelines for the whole of the public service on the steps needed to reorient towards a public service/customer focus using the guidance of the PWC report, ‘The Road Ahead.’

4 The State Services Commission (or its successor) develop mandatory guidelines for the whole of the public service on how to reorient towards a human rights compliant culture in policy and project development using the human rights approach recommended by the United Nations and developed for New Zealand by the Human Rights Commission.

5 The State Services Commission develop a model of community engagement that requires the focus to be on self-empowerment of the communities it serves. Public servants to be trained in cultural awareness of the communities they serve.

6 The State Services Commission:a. review and update the Code of Ethics for all public sector employees so that it is comprehensive though straightforward and contains examples of ethical conflicts employees may have.b. provide an ongoing training programme to public servants on conflicts of interests and ethics.c. provide guidance to public sector employees on how to identify conflicts of interest between an employee’s work and personal life and what to do when potential or actual conflicts arise. d. develop a clause akin to a restraint of trade clause in certain areas where government contracts with external persons and groups so that an employee cannot contract themselves back to the government until a period of between 2 to 5 years has lapsed since employment. e. develop an advice and disciplinary committee in relation to breaches of ethics so that there are consequences for a person breaching them or acting contrary to a Code of Ethics.

2 The proposed public service reform legislation provides that a key principle includes ‘service to the public’.

3 The State Services Commission (or its successor) develop mandatory guidelines for the whole of the public service on the steps needed to reorient towards a public service/customer focus using the guidance of the PWC report, ‘The Road Ahead.’

4 The State Services Commission (or its successor) develop mandatory guidelines for the whole of the public service on how to reorient towards a human rights compliant culture in policy and project development using the human rights approach recommended by the United Nations and developed for New Zealand by the Human Rights Commission.

5 The State Services Commission develop a model of community engagement that requires the focus to be on self-empowerment of the communities it serves. Public servants to be trained in cultural awareness of the communities they serve.

6 The State Services Commission:a. review and update the Code of Ethics for all public sector employees so that it is comprehensive though straightforward and contains examples of ethical conflicts employees may have.b. provide an ongoing training programme to public servants on conflicts of interests and ethics.c. provide guidance to public sector employees on how to identify conflicts of interest between an employee’s work and personal life and what to do when potential or actual conflicts arise. d. develop a clause akin to a restraint of trade clause in certain areas where government contracts with external persons and groups so that an employee cannot contract themselves back to the government until a period of between 2 to 5 years has lapsed since employment. e. develop an advice and disciplinary committee in relation to breaches of ethics so that there are consequences for a person breaching them or acting contrary to a Code of Ethics.

B Support of the Muslim Community in New Zealand

45 The Muslim community in New Zealand faces multiple unique challenges and has been failed by the public service. It has complex needs due to the language, culture, ethnic diversity and age distortion of its membership and the fact that it contains a high number of refugees. Cultural issues surrounding gender are different to and misunderstood by mainstream. Members experience serious problems of social isolation, marginalisation, discrimination in employment, bullying at schools and women face regular public expressions of Islamophobia directed towards them.

46 The public service’s inability to effectively provide for this community prior to the attacks has been a serious failing. Addressing their disadvantage requires multiple steps on multiple fronts. Because of their comparatively small size, they have lacked the clout which other marginalised groups have through numbers when it comes to being able to get the attention and resources of government. Furthermore, since the Christchurch attacks, the Muslim community has experienced trauma, fear and greater levels of vulnerability.

Recommendations on support of the Muslim community

7 A cross-government working group be immediately reactivated to work with a Muslim Sector Advisory Group to develop an across government plan to deliver urgent services to the New Zealand Muslim Community in the areas of youth services, education, employment health and welfare.

8 There be an immediate injection of funding to support the health and resilience of the New Zealand Muslim communities, with decisions on allocation being made jointly by the cross government working group and the Muslim Sector Advisory Group.

9 That WOWMA, as proven operator of successful Muslimah programmes, be immediately provided with specific and targeted funding for a five year period to continue to support young women from across the country to be empowered to reach their full potential rather than be blighted by the serious disadvantages they face.

10 Specific and targeted funding be made available to IWCNZ for a period of five years, to compensate for the five years IWCNZ has engaged with government on security and community issues, often at its own time and expense, without success.

C Security for the protection of all communities in Aotearoa/New Zealand

47 IWCNZ refers to para 287 to 311 of its submissions. It is evident that the Christchurch mosque attacker was not on the radar of the GCSB, SIS, DPMC and NZ Police until March 15, 2019. Those branches of government that were intended to protect citizens failed in detecting his intended actions with catastrophic consequences. 37

48 IWCNZ submits that reasons for this are multiple. In the period 2015 to 2019, the respective agencies were not taking seriously the threat to Muslim communities in New Zealand from known expressions of Islamophobia, the Alt Right and white supremacist groups (globally and in New Zealand). Rather, they were focussed solely on the Muslim community as the population from which the risks were coming. 38

49 That focus was in spite of the repeated advice given by IWCNZ to the SIS, the Minister and the Police, over this period, as to what was happening on the ground and the increasing expressions of concern. The obvious conclusion and one which IWCNZ draws is that:

(i) there was no or very little intelligence from the Five Eyes coalition partners backing up what was being said to the agencies by Muslims in New Zealand about the danger they felt under from Islamophobia. The Five Eyes were out of touch and out of date in their intelligence, without any or adequate focus on the Alt Right, despite the fact so much terrorism in the USA was coming from it. 39

(ii) the Muslim voice was not valued by the agencies in the same way that the voices of others were and this is likely to be as a result of a deep bias (conscious or unconscious) against Muslims. The fact that, after such a focus of surveillance on the Muslim community, there was no-one from within it who was trusted sufficiently by the security agencies to have a high security clearance, is an indicator that the agencies' advice was biased.

Disproportionate reliance on Five Eyes

50 The inadequate and biased intelligence coming from the Five Eyes coalition, and on which New Zealand has aligned its intelligence, has caused suffering, alienation and discrimination against the Muslim community. For example, three young Muslim men were arrested, charged, convicted and imprisoned in New Zealand as a result of sharing an ISIS video. It is understood that no persons sharing white supremacist videos, or inciting white supremacist actions against Muslims in New Zealand, were even under surveillance prior to the attacks. The differential treatment is unfair and disturbing as well as negligent. It has failed the Muslim community in New Zealand and failed New Zealand.

51 It is time to recognise the reality that the USA has major corporates embedded into its political system and, particularly in the Trump era it has different goals and priorities. It is unsafe for New Zealand, a small nation, to be solely reliant on Five Eyes intelligence. New Zealand needs to have, and be seen to have, a degree of independence in the international arena. It needs a range of alliances; not just one in which the dominant partner is the USA. It needs intelligence alliances in the Asia Pacific region where it is based and elsewhere. It needs better and more accurate and reliable intelligence.

52 IWCNZ says that New Zealand needs to leverage itself as a small but competent independent human rights compliant nation. It has the capacity to inspire others by its independence and strong human rights stands and be a much larger force for good on a global scale. This potential has manifested itself already since the Christchurch attacks.

53 IWCNZ says that the step taken by the Inspector General of Intelligence in creating an external intelligence group is an excellent one and should be made permanent. 40

It is an important means by which security agencies ensure they are operating in the world of real security threats and not caught out by institutional lag.

Surveillance via social media monitoring

54 It is understood that much surveillance happens via social media. However, without a sophisticated understanding of the values, culture and language of the Muslim community and how social media operates, social media monitoring by security agencies for Muslim terrorists (or any other suspect group for that matter) is fraught with risks of catching many innocent people in its net. 41

Gun ownership and hate speech 55 There is little oversight into the background of persons owning guns in New Zealand. It appears the killer had guns that he had bought lawfully. IWCNZ welcomes the legislation to outlaw semi-automatic guns with exceptions. However, further work needs to be done to develop a system where the background of applicants is checked for hate speech/hate crimes and membership of hate or supremacist groups before they are given a licence to own one gun or more. Once a license is issued, it should have to be renewed biennially and checks made again at each renewal. Reported instances of hate speech and hate crimes need to be checked against the gun register and a licence removed if a report is well established. There should be an appeal system to protect against arbitrary or malicious reporting. 56 The 2017 Intelligence and Security Act 2017 requires at s 3(c)(i) that the functions of the intelligence and security agencies are performed in accordance with …all human rights obligations recognised by New Zealand law. This is compatible with a human rights approach. However, given the powers and focus on New Zealand population inherent in the Act, it is vital that security agencies listen to and act to protect the Muslim community as potential victims.

Gun ownership and hate speech 55 There is little oversight into the background of persons owning guns in New Zealand. It appears the killer had guns that he had bought lawfully. IWCNZ welcomes the legislation to outlaw semi-automatic guns with exceptions. However, further work needs to be done to develop a system where the background of applicants is checked for hate speech/hate crimes and membership of hate or supremacist groups before they are given a licence to own one gun or more. Once a license is issued, it should have to be renewed biennially and checks made again at each renewal. Reported instances of hate speech and hate crimes need to be checked against the gun register and a licence removed if a report is well established. There should be an appeal system to protect against arbitrary or malicious reporting. 56 The 2017 Intelligence and Security Act 2017 requires at s 3(c)(i) that the functions of the intelligence and security agencies are performed in accordance with …all human rights obligations recognised by New Zealand law. This is compatible with a human rights approach. However, given the powers and focus on New Zealand population inherent in the Act, it is vital that security agencies listen to and act to protect the Muslim community as potential victims.

----

37 It is acknowledged that there is an element of speculation in this given the fact IWCNZ has not had access to any SIS material. However, it has been acknowledged publicly that the mass murderer was not on the radar of the SIS.38 This is the perception of IWCNZ supported by Nicky Hager in a 2003 article: Surveillance: Technological change, foreign pressures and over-reaction to terrorist threats at www.privacy.org.nz/assets/Files/13854584.pdf p 10: The target of expanded SIS “counter-terrorism” surveillance…. is New Zealand Muslim people. That is specifically whom the money was approved for. The increased Auckland surveillance and the new surveillance equipment are primarily to spy on mosques and New Zealanders who happen to be Muslim in the Auckland region. They would not admit it publicly, but the SIS and other New Zealand agencies are following the FBI and other US agencies in equating terrorism with people of Middle Eastern and Muslim descent. 39 See Paul Buchanan’s analysis (pre March 2019) of the delay in security agencies keeping abreast of real life security issues and dependence on Five Eyes ‘Institutional Lag and the New Zealand Intelligence Community’, Evening Report.nz 2016/03/09 40 See annual report www.igis.govt.nz/assets/Annual-Reports/Annual-Report-2019.pdf where the IG notes at [26] :It is well recognised internationally that best practice for oversight involves ensuring there are sufficient means for the oversight body to understand the scope of community views on issues relevant to intelligence agency oversight. It is important that oversight does not speak solely with specific interest groups or communities, e.g. the intelligence community, lawyers, or politicians. All of our Five Eyes counterparts, and many of our European colleagues, have developed “outreach” programmes, which involve multiple points of connection to community representatives… The Reference Group assists to keep us in touch with legal, social and security developments in New Zealand and overseas, and provides a thoughtful view on what it is most useful for an oversight body to communicate to the New Zealand public.41 See also New Zealand Law Commission report on Search and Surveillance 2012 at 11.59: the use of social media monitoring as a predictive tool may raise concerns about discrimination against certain ethnic or religious groups. Say, for instance, that an algorithm is used to scan social media for terms that might be used by terrorists associated with the so called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS). Those same terms may be used by Muslims in the legitimate expression of their religious beliefs. This may result in Muslims being subject to increased monitoring and investigation to confirm whether they are a threat or not. In turn, this may raise questions of discrimination on the grounds of religious beliefs and may discourage 11.56 11.57 11.58 11.59

Countering Violent Extremism

57 Despite a clear plan of action being developed by the United Nations in 2015, (para 75-77 Submissions) identifying steps needed to be taken by government to counter violent extremism, the New Zealand government, through the public sector including its security agencies, was primarily focussed on surveillance (of the Muslim community) with little in the way of a preventive strategy. What prevention projects that were underway were ineffective and apparently poorly funded. 42

58 There needs to be a coordinated and strategic national approach to prevention. A key solution to Muslim extremism in Muslim minority countries was always and still is to bring marginalized communities into mainstream; to give them opportunities to be participants in the society and to put funding into community engagement efforts. Investment must be made in bringing communities together.

59 There are several sources of information on how successful strategies would operate and what the key features would be. Recent examples only are set out here.

Canada

60 In February 2018 the Canadian House of Commons Report on Taking Action Against Systemic Racism and Religious Discrimination including Islamophobia was tabled. It recommended that the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage undertake a study and report its findings to the House on how the government could develop a whole of government approach to reducing or eliminating systemic racism and religious discrimination, including Islamophobia.

61 The Committee duly undertook the study recommended. 43 Ultimately, the Committee reported its findings and made 30 recommendations that were presented to the House in 2019. (check). 44

All suggestions by the witnesses interviewed, and outlined in the report, have since been adopted in some way, shape or form. Some relevant findings are referred to below:

A whole of Government approach

62 A “whole of government approach” was essential. 45 . A National Strategy must include direct and frequent consultation with communities affected. 46 It must take a community-based approach. 47 Key aspects of the National Strategy included that: 48

a. The needs of the people the government seeks to serve must be appropriately addressed. Therefore, a “race equity lens” should be developed as a key element;

b. Any projects adopted have clearly defined targets, deadlines and reporting mechanisms so as to be effective, sustainable and accountable; c. Every level of Government must be incorporated and have a plan to progress the National Strategy. Consequently, there needs to be a cross jurisdictional approach.

d. Public awareness and dialogue is instigated by the Government initiating a conversation about “understanding and diversity”; and

e. A targeted scheme is introduced into schools which includes in the curriculum “lessons on race, religion, diversity and related topics”.

Data collection

63 Data collection was pivotal. The Associate Deputy Minister of the Inclusion, Diversity and Anti-Racism Division of the Government of Ontario was cited as saying that where there is “no data”, there is a perception that there is “no problem” and therefore, there is “no solution”. 49

Research

64 Once data is collected, more substantial research needs to be undertaken. 50 Research grants should be established. Such research could be done by Government, civil society, researchers within the community and through investment in academic experts in universities to study the issues further. Institutions of professionals, such as the Political Science Institution could also be recipients of grants to undertake the work. This would ensure that policy-makers were informed with scholarly research which could withstand “the test of peer review”.

United Kingdom – ‘Contest’ and ‘Prevent’

65 The United Kingdom’s strategy on countering international terrorism (CONTEST) was released to Parliament in July 2006. 51 It was a response to the events of 9/11 and recognised the continuing and increasing risk of terrorist attacks in the United Kingdom. The major concern was that radicalised individuals were employing a distorted and unrepresentative version of the Islamic faith to justify violence. 52 CONTEST acknowledged that Muslim communities as a whole did not threaten security and, in fact, contributed greatly to the United Kingdom.

66 One of the four principal strands of CONTEST is PREVENT. PREVENT’s primary goal is to safeguard individuals from becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism. It seeks to pre-empt radicalism at an early stage and employs similar approaches used in deterring gang-affiliation or membership. PREVENT’s objectives, the level of importance attributed to each, and the measures employed to enable its success Data collection

(i) Engaging in the “battle of ideas”, which addresses the contributors to radicalisation, challenging, and responding to the ideological challenge that terrorism presents or is believed to justify, in particular, by assisting Muslims who wish to dispute those ideals to do so;

(ii) Providing early intervention and offering support to those most at risk of radicalisation through specialist tailored agencies; and

(iii) Deterring those who facilitate, and encourage others to engage in terrorism by changing the environment in which they operate, and to rehabilitate.

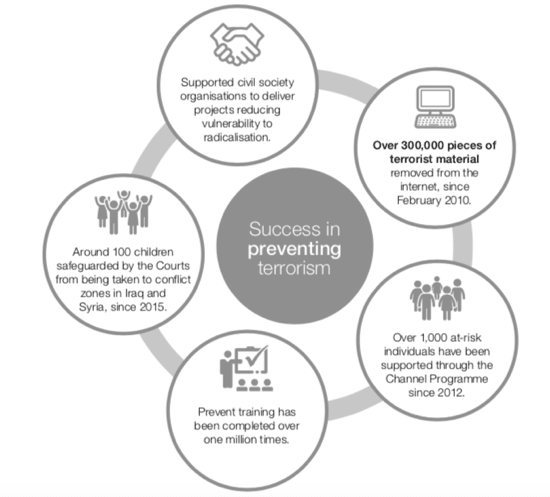

67 PREVENT relies heavily on leadership and partnerships, 53 employing a wide network across all sectors, public and private. The following figure, taken from a recent review of CONTEST, can be seen as providing encouragement for its success as a tool for reducing terrorism: 54

68 Some academics and commentators, however, have criticised PREVENT on the grounds that it results in:

(i) Over-surveillance of the Muslim community, which has increased Islamophobia, seen as the core of the PREVENT strand; 55

(ii) Encouragement to look for threats where they do not exist;

(iii) Increasing time spent with already radicalised individuals is giving them unwarranted professional respect;

(iv) Targeting of young members of a family rather than the elders as they are seen as easier to co-opt than the adults;

(v) Labelling of the strand as “toxic” due to opposition from Muslim groups; 56

(v) That pre-empting criminal extremism is “fundamentally flawed” and presents a “serious risk” of human rights violations; 57

69 The programme has seen two comprehensive reviews since 2003. First in 2011 58 and again in 2018 following the 2017 terrorist attacks in Manchester and London. 59 It continues as it is said to be important to maintain “coherent and sincere preventative efforts”. 60 The alternative is a reactive approach which carries potentially greater risks.

70 The Missing Muslims Report recommended consideration of the appointment of a ‘Prevent Ombudsman’, to develop definitions of nonviolent extremism and how to incorporate emerging evidence / best practice from overseas programmes that tackled extremism. The Casey Review 61 71 In 2015 the then Prime Minister and Home Secretary instructed Dame Louise Casey to undertake a review into integration and opportunity in isolated and deprived communities. 62 The findings were that discrimination and disadvantage were feeding a sense of grievance and unfairness. In some places there were high levels of social and economic isolation. 63 The solution to all the problems was to promote integration and tackle social exclusion. 64 Missing Muslims Report 72 In July 2017 a group called ‘Citizens UK,’ the largest and most diverse community organisation in the United Kingdom, released a report from ‘The Citizen’s Commission on Islam, Participation and Public Life’ which it had set up to inquire into '…how to unlock British Muslim Potential for the Benefit of All.' It was chaired by the Rt Hon, Dominic Grieve QC, former Attorney General. The report was entitled ‘The Missing Muslims’, report by the Citizens Commission on Islam, Participation and Public Life.

73 The Commission found that in areas of high deprivation, lack of integration was at its greatest. It identified structural barriers including a lack of economic opportunities and discrimination, which were particularly acute for Muslim women. Employers were already making headway on addressing issues around unconscious bias – affecting both British Muslims and other groups – within their organisations.

However, more needed to be done, not just to provide more equitable access to opportunities for British Muslims but to allow the British economy to harness their potential for the benefit of the country. Recommendations centred around integration strategies and included steps employers needed to take to counter unconscious bias.

IWCNZ views

74 The government strategic emphasis should be on Preventing Violent Extremism rather than Countering Violent Extremism. The emphasis must be on steps supporting integration of the Muslim community into mainstream rather than engaging in surveillance of it. This requires a many pronged approach, as set out in the nine point plan IWCNZ has already provided to the public service.

75 Funding of youth initiatives, mentoring programmes, equal employment opportunity initiatives are all critical. The Muslim community in New Zealand is, in many parts, marginalised, and has been for a sustained period.

76 Work must also be done in New Zealand to prevent violent extremism in the Alt Right communities from which white supremacist terrorists and killers arise.

69 The programme has seen two comprehensive reviews since 2003. First in 2011 58 and again in 2018 following the 2017 terrorist attacks in Manchester and London. 59 It continues as it is said to be important to maintain “coherent and sincere preventative efforts”. 60 The alternative is a reactive approach which carries potentially greater risks.

70 The Missing Muslims Report recommended consideration of the appointment of a ‘Prevent Ombudsman’, to develop definitions of nonviolent extremism and how to incorporate emerging evidence / best practice from overseas programmes that tackled extremism. The Casey Review 61 71 In 2015 the then Prime Minister and Home Secretary instructed Dame Louise Casey to undertake a review into integration and opportunity in isolated and deprived communities. 62 The findings were that discrimination and disadvantage were feeding a sense of grievance and unfairness. In some places there were high levels of social and economic isolation. 63 The solution to all the problems was to promote integration and tackle social exclusion. 64 Missing Muslims Report 72 In July 2017 a group called ‘Citizens UK,’ the largest and most diverse community organisation in the United Kingdom, released a report from ‘The Citizen’s Commission on Islam, Participation and Public Life’ which it had set up to inquire into '…how to unlock British Muslim Potential for the Benefit of All.' It was chaired by the Rt Hon, Dominic Grieve QC, former Attorney General. The report was entitled ‘The Missing Muslims’, report by the Citizens Commission on Islam, Participation and Public Life.

73 The Commission found that in areas of high deprivation, lack of integration was at its greatest. It identified structural barriers including a lack of economic opportunities and discrimination, which were particularly acute for Muslim women. Employers were already making headway on addressing issues around unconscious bias – affecting both British Muslims and other groups – within their organisations.

However, more needed to be done, not just to provide more equitable access to opportunities for British Muslims but to allow the British economy to harness their potential for the benefit of the country. Recommendations centred around integration strategies and included steps employers needed to take to counter unconscious bias.

IWCNZ views

74 The government strategic emphasis should be on Preventing Violent Extremism rather than Countering Violent Extremism. The emphasis must be on steps supporting integration of the Muslim community into mainstream rather than engaging in surveillance of it. This requires a many pronged approach, as set out in the nine point plan IWCNZ has already provided to the public service.

75 Funding of youth initiatives, mentoring programmes, equal employment opportunity initiatives are all critical. The Muslim community in New Zealand is, in many parts, marginalised, and has been for a sustained period.

76 Work must also be done in New Zealand to prevent violent extremism in the Alt Right communities from which white supremacist terrorists and killers arise.

----

42 IWCNZ does not have information relating to government allocations of CVE money for prevention prior to the mosque attacks.